An inspirational quote comes from the famous automaker Henry Ford.

An inspirational quote comes from the famous automaker Henry Ford.

“When everything seems to be going against you, remember that the airplane takes off against the wind, not with it.”

We often view adversity as an obstacle. Something negative which we must overcome or turn our backs upon. However, the times when we pit our our inner strength or our physical ability against adversity become the moments we can look back upon and see how they affected us and how we grew as a result. The things we learned to do and not to do. Wisdom gained from a bad experience or a positive encounter. Life lessons remembered. Through our struggles we can find defintion in our lives and become more than who we were in the beginning.

I’ve had some pretty good adventures and some harrowing experiences along with them. Looking back at all the things I have done, the most successful moments were those filled with adversity. The times when I had to grab hold of my bootstraps and drag each foot through the mud and mire to get through a particularly difficult moment that life threw at me. Where I ended up was not always where I planned to go, but it always gave me a start in a new direction.

My aspirations while growing up in small town America during the 1960s and 70s never included becoming a writer. Of everything I hoped to become, I can’t ever remember a desire to write for a living. Yet writing was one of the two things I loved to do more than anything else—reading and writing.

For my eleventh or twelfth birthday, exactly which has blurred into the past, a gift from a favorite aunt and uncle contained two books from a childhood series. My good friend was there for my birthday supper and the cake and ice cream that followed. When I opened the wrapping paper and found the books, I immediately invited my friend to choose one so we could sit down and read.

I recall that his response was somewhat less than enthusiastic.

Adversity. Life is what we make of it. Second and third grade were almost magical for me. Two supportive teachers gave a fidgety kid the tools needed to survive an endlessly repetitive environment where even the math problems were repeated over and over again with boring regularity. Two plus three. There are two pencils over here and three pencils over there. How many pencils are there?

Incredibly, no matter how many times you do the math, the answer always comes up five. Who does not understand this? And guess what. It does not even matter if you are adding oranges, bipeds, or earthworms. Third grade added some interest. If you have x number of piles of some object, and y number of objects in each pile, you can skip all the adding and just multiply. Numerous applications, but it’s still all the same.

To break up the monotony, I invented new ways to do math in my head. One of the first was utilizing the handy dandy multiply by ten system and then subtract or add any difference.

A favorite movie moment occurs in “Short Circuit” when Stephanie gives Number Five a dictionary and he begins reading for the very first time. “Ahhh! Input! More input!” And he gobbled it up in great gulps like a dessert traveler arriving at the oasis and finding the water sweet and pure. A later scene shows him surrounded by books and tossing one after another over his shoulder as he reaches for the next one to absorb, but there are no more.

–More Input–

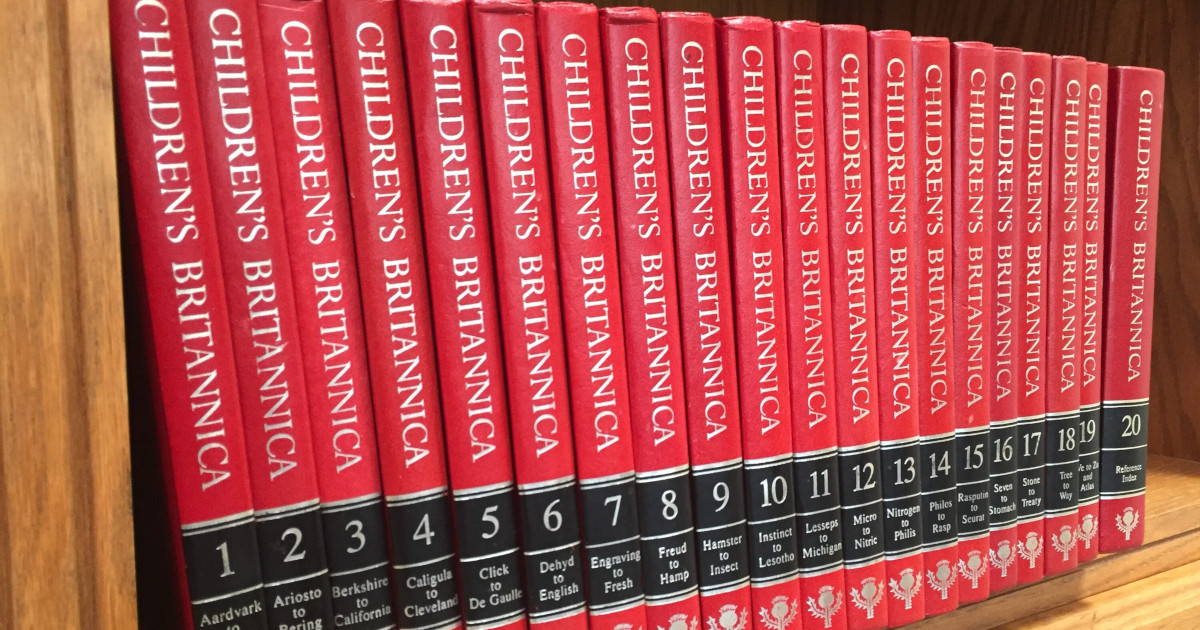

Because I read everything I could get my hands on, and an entire work of the Encyclopedia Britannica for Children sat on my dresser between neat bookends, and the far more extensive adult version on the living room bookshelf, there was a nearly endless supply of input to absorb. At least for a while. Britannica opened the doors to a world I knew was out there, but was just beginning to discover. When I started reading a National Geographic in a doctor’s office and wanted to take it with me, Mom got a subscription and added another window into the world.

Here, in this very moment as I write this, I realize that perhaps I was so absorbed with reading, that I forgot discovering how much I loved to write in third grade.

Adversity arrived in fourth grade in a new town, a new school, and yet another teacher. Unfortunately, she did not understand a fidgety young boy who rarely forgot anything. When I corrected a point she made in the geography portion of class based on something read in my encyclopedia, she dismissed it offhand and then proceeded to point out that she was the teacher and I the student. From that moment forward, how was I to trust anything she claimed was true unless I had further proof?

I rebelled. With my trusty resource at hand, she could never withstand the onslaught my young mind so deviously and carefully designed. First I stopped reading my geography book. No homework was turned in. She kept me after school for fifteen minutes, but got nowhere. Next was a phone call to my parents which resulted in an invitation to stop by on a Saturday afternoon to discuss it with me.

When Miss Teach was ensconced in a comfortable chair with a cup of coffee and perhaps a slice of my mother’s homemade nut bread, the inevitable question was brought forth, probably by my father. “Why aren’t you doing your homework and reading your geography book?”

I pointed an accusing finger. “She tells lies about it.”

My mother was aghast and my father stunned. I can only imagine the look on the teacher’s face because I could not look at her and have any hope to win. My first hurdle was enduring the inevitable chastisement.

“Don’t point and that isn’t how you talk to teachers and adults. You don’t call them liars.”

I was ready. “The ceiling is going to fall on us because of it,” I said in my very best matter-of-fact voice. “It’s all full of cracks already and I’ll be buried.”

Yet, I could not meet their faces. My own face felt hot and I’m sure it was quite red. I had actually imagined the old school with the fifteen-foot ceilings falling in, but I certainly knew it wasn’t going to happen. It came from a book I read. One of the main characters declared that if he walked into church the roof would cave in. Private Catholic grade school. Protestant teacher belittling children. It made sense to me, though I’m sure no one else got it and I had already pushed too far past acceptable limits to explain further.

(Be careful what you teach to a child. They are probably listening and processing in ways you can’t even imagine. What little I knew about protestants at the time amounted to believing they were nothing short of evil beings determined to wreak havoc, hell, and brimstone upon the world. An unfortunate viewpoint acquired from an old, cranky neighbor and reinforced by my experience with this teacher that I’ve since abandoned.)

The teacher said the paint and plaster were cracked, but the ceiling would not fall in and if it did, we’d be on top because we were on the top floor.

“What about geography?” My father wanted to know.

“She’s wrong about it. I’m not writing the lies because you said don’t lie.”

Dad wanted an explanation and I gave the best a four grader could muster with proof from my beloved encyclopedia. The teacher was flabbergasted and tried to defend herself, but over the course of my own defense, Dad realized she had maligned me in front of the entire class. Made fun of me is what she did. The afternoon meeting at home did not end well for her and my father demanded she apologize to me, which she fumbled in a big way in front of my parents. Another apology was to happen in class, but that was never delivered.

For my part, I had to start reading the geography book and turn in my homework on time. Somehow, I realized she was not going to force another meeting and didn’t bother to turn in nearly a month of missing worksheets. I survived the rest of the second semester and was passed on to the fifth grade with decent marks on my report card.

She almost never called on me in class again. I read my books, the magazine swiped from the doctor’s office, and a handful of pulp fiction crime novels replete with absurdly lewd imagery (‘he looked up and her bosom had become disarranged.’) of which my mother had no idea I somehow possessed and read.

Oh, the scandal if someone had caught me. But I sat in back, geography book open and the illicit reading material hidden from her view. While the other boys shot spitballs out of disassembled Bic pens, I perused the latest issue of Boy’s Life or a scavenged copy of True Detective.

Oddly enough, I cannot remember anything at all regarding math, science, or English from that year. Nothing. I could tell you about recess and playing kickball or basketball or digging trenches with our boots in the ice-covered playground that spring to drain the big puddles that formed. There was my brother (a year behind me) collapsing in a faint because it was too hot at daily Mass. Thirty below outside, ninety inside and all of us wearing thermal underwear under heavy wool clothes.

I learned three things from my experience in fourth grade that stayed with me through childhood and to this very day. Not just in that moment, but over time as grew from a young boy into a man.

Adults are not always right and in fact, some are wrong quite often. This humbles me, though admittedly I am not very humble, and reminds me that inevitably I will make mistakes. I try hard to recognize my errors and admit them to myself and to others. I strive to know the truth and to speak it. A part of that is admitting your mistakes.

There are those who would belittle a child for knowing something they did not. They don’t care about children and only pretend to care about others. It doesn’t bother them to hurt someone just to build themselves up. If you can’t trust them to care about a child’s feelings, how can you trust them with anything at all?

It is okay to face the wind and let it lift you higher. Don’t follow those who would force you to run with the wind and not against it just because it’s easier. Face your adversaries and let their wind lift you high above them. They will never lift off the ground and soar like an eagle. Their bitter instinct to hold you down results from a vain attempt to build themselves up.

Three truths that add up to a single tenant. Truth is often adversarial, but overcoming adversity is how we grow. How hard to admit you are wrong after the absolute certainty that you were right in the beginning? If you don’t admit your mistakes to yourself and to others, you are simply running with the wind and will never get off the ground.

To soar, we must turn to face life’s adversities and overcome them. Run against the wind.

The words of Henry Ford ring true. “When everything seems to be going against you, remember that the airplane takes off against the wind, not with it.”

Face the wind. Take off and soar.